Black youth are experiencing more social and economic isolation and immobility than ever before. Limited access to quality education, employment opportunities, and generational wealth transfer, have been pervasively out of reach for black youth. Crippling economic inequality has stagnated the potential to achieve financial stability compared to other communities, and prior generations.  Black youths historically inherit the repercussions of failing- underfunded schools, lacking and subpar resources, and overt discrimination. This culture of unrelenting socio-economic pressure has imploded communal cohesion, and degraded the collective communal values. The behavioral response to the disfunction has perplexed most observers, uneased by the provocative and unhinged conduct of today’s black teenagers. Limited education opportunities have deterred their long-term prospects and socio-economic mobility. Furthermore, discrimination in hiring practices, limited access to job networks, and occupational segregation, restrict their opportunities for economic advancement.

Black youths historically inherit the repercussions of failing- underfunded schools, lacking and subpar resources, and overt discrimination. This culture of unrelenting socio-economic pressure has imploded communal cohesion, and degraded the collective communal values. The behavioral response to the disfunction has perplexed most observers, uneased by the provocative and unhinged conduct of today’s black teenagers. Limited education opportunities have deterred their long-term prospects and socio-economic mobility. Furthermore, discrimination in hiring practices, limited access to job networks, and occupational segregation, restrict their opportunities for economic advancement.

The purpose of this article is not to inflame racial tension in a contentious environment.

Rather, it is to maintain a serious conversation about how to return a community on decline, back to prominence.

Black youth are also disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system, facing higher rates of arrest, incarceration, and involvement in the juvenile justice system.  The stigma and collateral consequences of criminal records severely limit their educational and employment prospects, perpetuating cycles of poverty and disadvantage. The behavioral aspect of today’s black youth has presents a plethora of issues, requiring a tempered approach. Mental health, and behavior issues with black adolescents, have distinct undertones related to the availability of adequate healthcare and youth outreach. Health disparities are seriously prevalent amongst black youth, including higher rates of chronic diseases, limited access to healthcare services, and exposure to environmental hazards. Health disparities impact their overall well-being and ability to thrive in various aspects of life. The dissolution of shifting economies, has also exasperated the dissipating social-health fabric meant maintain the cohesion of the community. More and more black youth experience homelessness, drug addiction, economic desperation, and extreme mental illness. Addressing the challenges faced by black youth requires comprehensive and systematic solutions, including investments in education, economic opportunities, criminal justice reform, healthcare access, and addressing structural racism and systematic discrimination.

The stigma and collateral consequences of criminal records severely limit their educational and employment prospects, perpetuating cycles of poverty and disadvantage. The behavioral aspect of today’s black youth has presents a plethora of issues, requiring a tempered approach. Mental health, and behavior issues with black adolescents, have distinct undertones related to the availability of adequate healthcare and youth outreach. Health disparities are seriously prevalent amongst black youth, including higher rates of chronic diseases, limited access to healthcare services, and exposure to environmental hazards. Health disparities impact their overall well-being and ability to thrive in various aspects of life. The dissolution of shifting economies, has also exasperated the dissipating social-health fabric meant maintain the cohesion of the community. More and more black youth experience homelessness, drug addiction, economic desperation, and extreme mental illness. Addressing the challenges faced by black youth requires comprehensive and systematic solutions, including investments in education, economic opportunities, criminal justice reform, healthcare access, and addressing structural racism and systematic discrimination.

How Do We Preserve

Our Peace

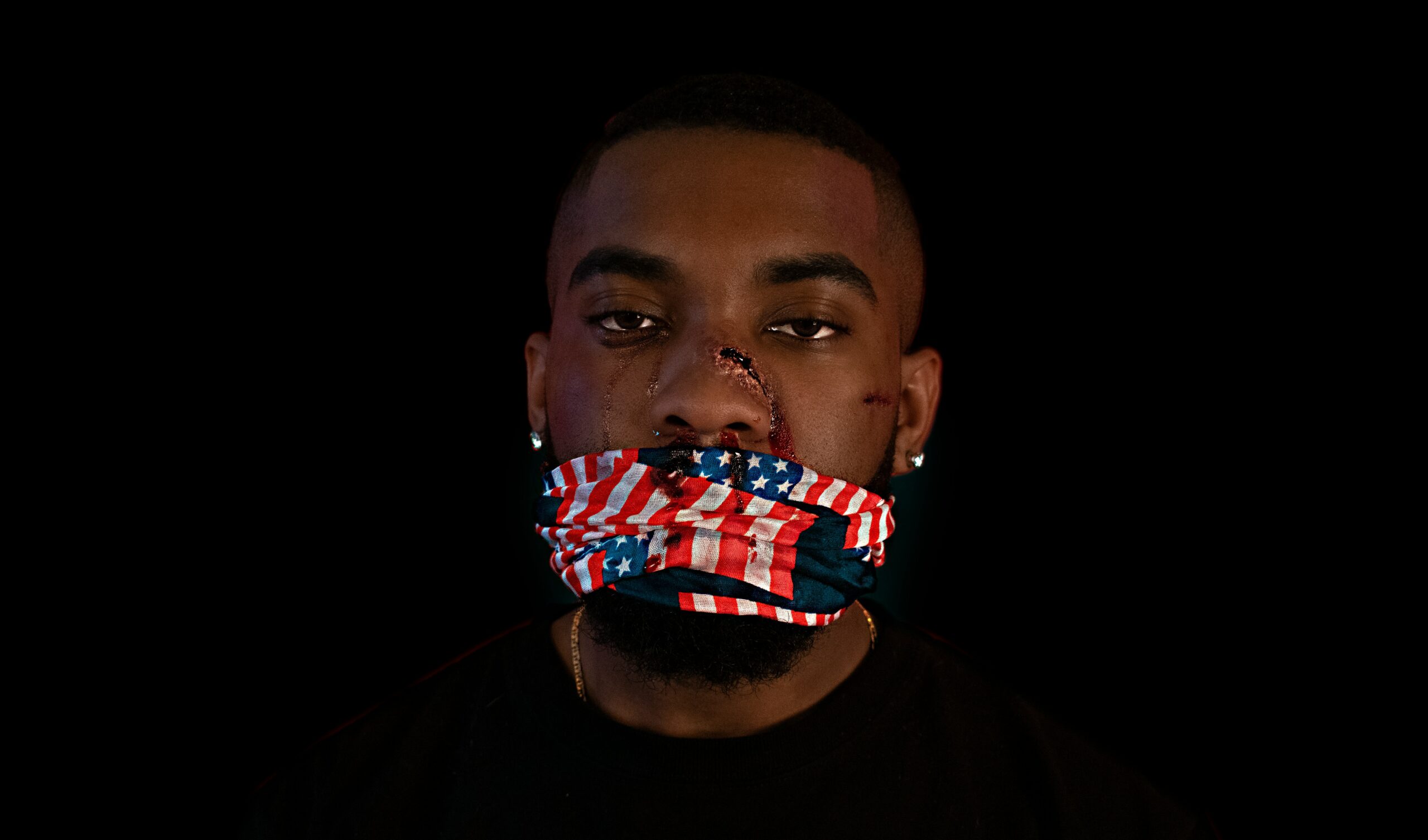

law enforcement has been a “hot-button issue” for the black community to address. Non-compliance versus over-policing, has been a contentious point for years, and the constant debate over black “self-autonomy,” has had a degrading effect on clear social reasoning, with paralyzing arguments that negate black pain and existence. The generational mistrust between law enforcement and communities of color is hardwired to the social experience of black and brown people. There is a credible link to the current “no-snitching culture,” and the government surveillance and repression of the 1960s’. COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) was a covert FBI operation targeting civil rights groups like the Black Panthers, MLK, SNCC, and others from the 1950s–1970s. Black communities saw firsthand how snitches were weaponized to dismantle organizations, assassinate leaders, and sow paranoia. The program used informants, infiltrators, and disinformation to destroy movements from within, which in turn, manifested a deep and generational distrust of law enforcement and the legal system. Law enforcement’s militarized tactics have been seen, not only as unjust, but actively harmful, urging communities of color to develop different ways of dealing with police.

There is a credible link to the current “no-snitching culture,” and the government surveillance and repression of the 1960s’. COINTELPRO (Counter Intelligence Program) was a covert FBI operation targeting civil rights groups like the Black Panthers, MLK, SNCC, and others from the 1950s–1970s. Black communities saw firsthand how snitches were weaponized to dismantle organizations, assassinate leaders, and sow paranoia. The program used informants, infiltrators, and disinformation to destroy movements from within, which in turn, manifested a deep and generational distrust of law enforcement and the legal system. Law enforcement’s militarized tactics have been seen, not only as unjust, but actively harmful, urging communities of color to develop different ways of dealing with police.

For decades, law enforcement in Black neighborhoods was characterized like that of an occupying force. Over-policing for minor offenses, under-policing for protection or justice, violence and racial profiling, became the norm in black and impoverished neighborhoods.  And many communities of color are familiar with the “parent-child” sit down about how to handle themselves during a police encounter. Coinciding with cameraphones and modular recording devices, theres been an effort to hold law enforcement officials accountable for unjustified traffic stops and unprovoked encounters, however this is seen as antagonistic by police, potentially scaling up the hostility. It is important to understand the “measure of mortality,” when dealing with law enforcement officials, especially those who seem aggressive and even antagonistic. Black drivers are about three times more likely to face pre-textual stops (e.g., for minor infractions) and five times more likely to be searched during such stops compared to white drivers.

And many communities of color are familiar with the “parent-child” sit down about how to handle themselves during a police encounter. Coinciding with cameraphones and modular recording devices, theres been an effort to hold law enforcement officials accountable for unjustified traffic stops and unprovoked encounters, however this is seen as antagonistic by police, potentially scaling up the hostility. It is important to understand the “measure of mortality,” when dealing with law enforcement officials, especially those who seem aggressive and even antagonistic. Black drivers are about three times more likely to face pre-textual stops (e.g., for minor infractions) and five times more likely to be searched during such stops compared to white drivers.  According to Bureau of Justice Statistics data, Black and Hispanic motorists are more likely to be searched or arrested (6%) compared to other groups (4%). Meanwhile, white drivers were less likely to receive citations, and Black drivers were least likely to receive a warning (34% vs. 47% for whites). Black drivers also report more frequent use or threat of force by police (20% vs. 2% for whites). Black men in the U.S. face a staggering lifetime risk of being killed by police: approximately 1 in 1,000, while the rate for all men is about 1 in 2,000, and for women, it’s around 1 in 33,000. Additional research shows Black Americans are 2.5 to 3.5 times more likely to die from police violence than white Americans. Police use of force ranks as a leading cause of death for men aged 25–29, across racial groups, though the impact is much greater on Black young men.

According to Bureau of Justice Statistics data, Black and Hispanic motorists are more likely to be searched or arrested (6%) compared to other groups (4%). Meanwhile, white drivers were less likely to receive citations, and Black drivers were least likely to receive a warning (34% vs. 47% for whites). Black drivers also report more frequent use or threat of force by police (20% vs. 2% for whites). Black men in the U.S. face a staggering lifetime risk of being killed by police: approximately 1 in 1,000, while the rate for all men is about 1 in 2,000, and for women, it’s around 1 in 33,000. Additional research shows Black Americans are 2.5 to 3.5 times more likely to die from police violence than white Americans. Police use of force ranks as a leading cause of death for men aged 25–29, across racial groups, though the impact is much greater on Black young men.

How Do We

Protect Ourselves

asset forfeiture has disproportionately affected Black communities for years. Asset forfeiture is a legal process through which law enforcement agencies seize assets that are suspected to be involved in or derived from criminal activity.  This can include cash, vehicles, real estate, and other valuables, which for Black families and individuals, the loss of such assets can be devastating, contributing to further economic instability. The practice has faced significant scrutiny and criticism, particularly regarding its impact on Black communities in the United States. Research has shown that Black Americans are more likely to have their assets seized than White Americans, even when rates of criminal activity are similar. For Black entrepreneurs and business owners, asset forfeiture can pose significant threat. Seizure of business assets or funds can disrupt operations, hinder growth opportunities, and undermine efforts to build generational wealth. Unwarranted forfeiture erodes trust between law enforcement agencies and Black communities. The aggressive policing practices in low-income and minority neighborhoods usually coincide with the targeted asset forfeiture and appropriation of valuables from Black individuals, in-spite of whether they have been suspected of a crime or not. Civil forfeiture laws allow law enforcement to seize property suspected of being connected to a crime,

This can include cash, vehicles, real estate, and other valuables, which for Black families and individuals, the loss of such assets can be devastating, contributing to further economic instability. The practice has faced significant scrutiny and criticism, particularly regarding its impact on Black communities in the United States. Research has shown that Black Americans are more likely to have their assets seized than White Americans, even when rates of criminal activity are similar. For Black entrepreneurs and business owners, asset forfeiture can pose significant threat. Seizure of business assets or funds can disrupt operations, hinder growth opportunities, and undermine efforts to build generational wealth. Unwarranted forfeiture erodes trust between law enforcement agencies and Black communities. The aggressive policing practices in low-income and minority neighborhoods usually coincide with the targeted asset forfeiture and appropriation of valuables from Black individuals, in-spite of whether they have been suspected of a crime or not. Civil forfeiture laws allow law enforcement to seize property suspected of being connected to a crime,  often without requiring a criminal conviction. This leads to abuse and targeting of vulnerable communities. The limited due process rights afforded to individuals whose assets are seized, is where the criminal intent of law enforcement comes into question. “Was I a target? Is this legal? How much do they know? The invasive nature of a forfeiture becomes an even more complex question, as innocent individuals attempt to prove their innocence to reclaim their property, and get back to a sense of normalcy. Broader civil liberties concerns about government overreach and property rights further uproot trust between law enforcement and communities, particularly in communities of color already grappling with issues of racial profiling. Asset forfeiture creates a perverse incentive for law enforcement agencies to prioritize revenue generation over public safety. Seized assets often directly fund law enforcement budgets and bonuses, leading to potential conflicts of interest and abuses. Advocates for reform argue that meaningful change from policymakers, can build towards reducing the adverse impact of asset forfeiture on Black wealth, protecting individuals’ rights, and promote economic equity and equality within Black communities.

often without requiring a criminal conviction. This leads to abuse and targeting of vulnerable communities. The limited due process rights afforded to individuals whose assets are seized, is where the criminal intent of law enforcement comes into question. “Was I a target? Is this legal? How much do they know? The invasive nature of a forfeiture becomes an even more complex question, as innocent individuals attempt to prove their innocence to reclaim their property, and get back to a sense of normalcy. Broader civil liberties concerns about government overreach and property rights further uproot trust between law enforcement and communities, particularly in communities of color already grappling with issues of racial profiling. Asset forfeiture creates a perverse incentive for law enforcement agencies to prioritize revenue generation over public safety. Seized assets often directly fund law enforcement budgets and bonuses, leading to potential conflicts of interest and abuses. Advocates for reform argue that meaningful change from policymakers, can build towards reducing the adverse impact of asset forfeiture on Black wealth, protecting individuals’ rights, and promote economic equity and equality within Black communities.

How Do We Obtain More

For Ourselves

immigration has become increasingly contentious. Therefore, it is important to understand its complex effects on Black wealth and community. Metropolitan demographics are transforming—driven not just by immigration, but also by economic shifts, labor-market dynamics, and changing social policies. As diverse communities settle into urban areas, coexistence becomes more complex, influencing and fluctuating access to opportunities.  Studies suggest that when immigrant populations in a specific skill bracket increase by 10%, wages for Black workers in that group tend to drop by around 4%, while employment rates fall by 3.5 percentage points—and incarceration rates rise by nearly one full percentage point. More comprehensive analysis estimates that, between 1980 and 2000, immigration accounted for 20–60% of the decline in wages, 25% of the drop in employment, and 10% of the increase in incarceration among lower-skilled Black men.

Studies suggest that when immigrant populations in a specific skill bracket increase by 10%, wages for Black workers in that group tend to drop by around 4%, while employment rates fall by 3.5 percentage points—and incarceration rates rise by nearly one full percentage point. More comprehensive analysis estimates that, between 1980 and 2000, immigration accounted for 20–60% of the decline in wages, 25% of the drop in employment, and 10% of the increase in incarceration among lower-skilled Black men.  Other estimates show wage reductions of 8.3% for Black high school dropouts, and employment declines of 7.4 percentage points, during the same period. Beyond competition in low-skill sectors, both Black and immigrant workers often languish in occupational segregation, facing limited access to higher-paying roles. Meanwhile, entrepreneurial activity among immigrants—particularly from African and Caribbean nations—offers vibrancy and jobs in underserved neighborhoods. In 2018, Black immigrant households alone generated $133.6 billion in income, paid $36 billion in federal and state taxes, and retained $97.6 billion in spending power. Yet Black-owned businesses still face persistent challenges: only around 3.3% of all employer firms are Black-owned—far below the 14.4% share of the national population—and there remains vast disparity in resources and access.

Other estimates show wage reductions of 8.3% for Black high school dropouts, and employment declines of 7.4 percentage points, during the same period. Beyond competition in low-skill sectors, both Black and immigrant workers often languish in occupational segregation, facing limited access to higher-paying roles. Meanwhile, entrepreneurial activity among immigrants—particularly from African and Caribbean nations—offers vibrancy and jobs in underserved neighborhoods. In 2018, Black immigrant households alone generated $133.6 billion in income, paid $36 billion in federal and state taxes, and retained $97.6 billion in spending power. Yet Black-owned businesses still face persistent challenges: only around 3.3% of all employer firms are Black-owned—far below the 14.4% share of the national population—and there remains vast disparity in resources and access.  Even though Black entrepreneurship has surged—employer businesses grew nearly 57% from 2017 to 2022—Black firms still harness just a small slice of economic ownership. Immigration policies also shape access to public resources. Undocumented families may be shut out from vital social services—from healthcare to housing—which strains community networks and increases precarity. Meanwhile, urban restructuring and gentrification shift resources and opportunities away from historically Black neighborhoods, deepening inequities. The relationship between immigration and Black wealth is neither straightforward nor one-sided. Immigration can exacerbate wage competition and resource scarcity, yet can bring entrepreneurial energy and economic growth. In the face of such tensions, forging a collective identity rooted in shared prosperity is essential—not only for unity, but for equitable advancement.

Even though Black entrepreneurship has surged—employer businesses grew nearly 57% from 2017 to 2022—Black firms still harness just a small slice of economic ownership. Immigration policies also shape access to public resources. Undocumented families may be shut out from vital social services—from healthcare to housing—which strains community networks and increases precarity. Meanwhile, urban restructuring and gentrification shift resources and opportunities away from historically Black neighborhoods, deepening inequities. The relationship between immigration and Black wealth is neither straightforward nor one-sided. Immigration can exacerbate wage competition and resource scarcity, yet can bring entrepreneurial energy and economic growth. In the face of such tensions, forging a collective identity rooted in shared prosperity is essential—not only for unity, but for equitable advancement.

How Do We Get Back To

Caring For Each Other

education for Black youth is under direct threat. Rising social and economic immobility, combined with chronically underperforming public schools, has fueled what many call the “school-to-prison pipeline.” In classrooms, behavioral tensions collide with the frustrations of undervalued and underpaid teachers, eroding community progress. Black youth have long faced the instability of underfunded schools with scarce resources—but today, that challenge is compounded by overt policy decisions. Some state officials have removed lessons on race relations and American slavery from curricula, deliberately obscuring the struggles and contributions of African Americans. This calculated restriction undermines collective understanding and denies students the historical context necessary to grasp the conditions of the Black community. Under relentless socio-economic pressure, the value placed on education has eroded, leaving young people vulnerable to the consequences of disengagement. Rising crime rates among younger Black teenagers reflect a community staggered by these systemic assaults, as limited educational opportunities block long-term prospects and upward mobility. Discrimination in hiring, lack of access to job networks, and occupational segregation further entrench these inequalities, restricting pathways to social, economic, and educational advancement.

Black youth have long faced the instability of underfunded schools with scarce resources—but today, that challenge is compounded by overt policy decisions. Some state officials have removed lessons on race relations and American slavery from curricula, deliberately obscuring the struggles and contributions of African Americans. This calculated restriction undermines collective understanding and denies students the historical context necessary to grasp the conditions of the Black community. Under relentless socio-economic pressure, the value placed on education has eroded, leaving young people vulnerable to the consequences of disengagement. Rising crime rates among younger Black teenagers reflect a community staggered by these systemic assaults, as limited educational opportunities block long-term prospects and upward mobility. Discrimination in hiring, lack of access to job networks, and occupational segregation further entrench these inequalities, restricting pathways to social, economic, and educational advancement.

The current average for black wealth tops out at just over $200,000 compared to white households who maintain just over $1,000,000 on average. These disparaging statistics alone magnify the need for decisive and immediate financial change in the black community, or risk being rendered completely impotent in the larger global market. As our economic change, it is critical to develop and diversify ways to grow our own money, while retaining our independence and right to self-determination. As the study shows, 2053 is the year in which the black community could reach full depletion of transferable wealth, if there is no federal supplement, or internal change within America’s black households. We should all be worried.

The current average for black wealth tops out at just over $200,000 compared to white households who maintain just over $1,000,000 on average. These disparaging statistics alone magnify the need for decisive and immediate financial change in the black community, or risk being rendered completely impotent in the larger global market. As our economic change, it is critical to develop and diversify ways to grow our own money, while retaining our independence and right to self-determination. As the study shows, 2053 is the year in which the black community could reach full depletion of transferable wealth, if there is no federal supplement, or internal change within America’s black households. We should all be worried.